Frans David Oerder (1867 - 1944)

Portrait of a Zulu

Signed and dated upper left: F.D. Oerder / ‘97

Oil on canvas

53 x 42.9 cm. (20 ¾ x 16 ¾ in.)

Portrait of a Zulu

Signed and dated upper left: F.D. Oerder / ‘97

Oil on canvas

53 x 42.9 cm. (20 ¾ x 16 ¾ in.)

Frans David Oerder’s portrait of a Zulu man, one of a small group of works painted by the artist during his trip to Zululand in 1897-98, surely counts amongst the finest portraits painted in South Africa in the late 19thcentury. Painted at a tumultuous moment in South Africa’s history, the picture is highly important in being one of the earliest, non-ethnographic, portraits of a Zulu painted by a European artist.

Oerder was born in the Netherlands, studying at the Rotterdam Academy from 1880 to 1885 and winning the prestigious King William III Gold Medal and Bursary. Following further study in Italy and Belgium, the young artist moved to Pretoria in 1890, then the capital of the precariously independent Boer Transvaal Republic. Opportunities were initially very hard to come by and Oerder first worked as a house painter, before getting a job painting poles along the Delagoa Bay railway line. In 1894 he took a teaching post at a school in Pretoria, eking out a living on the side as a newspaper cartoonist.

In late 1897 and early 1898, with war brewing, Oerder went on a trip to Zululand, finishing about thirty oil paintings depicting the Zulu people and their way of life. These are amongst the most beautiful and important works of his career. With the outbreak of the Second Anglo-Boer War in 1899 Oerder was appointed to the post of official war artist by the Boer President Paul Kruger, though was soon captured by the British and interned in the prisoner of war camp at Meintjeskop. Following his release in 1903, Oerder travelled the East African coast and in 1905 he was elected a member of the South African Society of Artists, leading to numerous important landscape and portrait commissions. However, finding post-war conditions in South Africa difficult, with Pretoria having been annexed by the British in 1902, Oerder decided to return to the Netherlands in 1908, eventually marrying and settling in Amsterdam. During this stable period Oerder focussed primarily, and successfully, on floral still lifes. In 1938 Oerder returned to Pretoria, where his work was now highly acclaimed, remaining there for the last six years of his life.

Fig. 1, Frans David Oerder, My Gardener, oil on canvas,

40.5 x 30.4 cm, Private Collection

Oerder’s early South African works of the 1890s reflect the artist’s exposure to the Dutch masters and the French Impressionists and marked him out as the leading artistic talent then active in South Africa, alongside his friend, the sculptor Anton van Wrouw. These works, consisting largely of genre scenes and landscapes, are the first paintings to authentically capture the Transvaal. Yet, as attractive as these are, it is Oerder’s rarer portraits of indigenous South Africans, comparatively little studied within his oeuvre, which should today be considered as his most significant artistic undertakings (fig. 1).

The present work was painted in late 1897 in Zululand. Zululand, to the north-east of Durban, was the area encompassed by the Zulu Kingdom, which had risen to prominence in the early 19th century under Shaka Zulu. By the time Oerder visited, the Kingdom had ceased to function as an independent entity, having been incorporated by the British into the Colony of Natal following the Anglo-Zulu War of 1879. The bravery and military ingenuity displayed by the Zulu in fierce battles such as Isandlwanda, Rorke’s Drift and Ulundi ensured that the war, and the Zulu people, immediately became legendary in the British imagination. Oerder’s portrait would surely therefore have had wide appeal when exhibited in either Cape Town or Pretoria on his return.

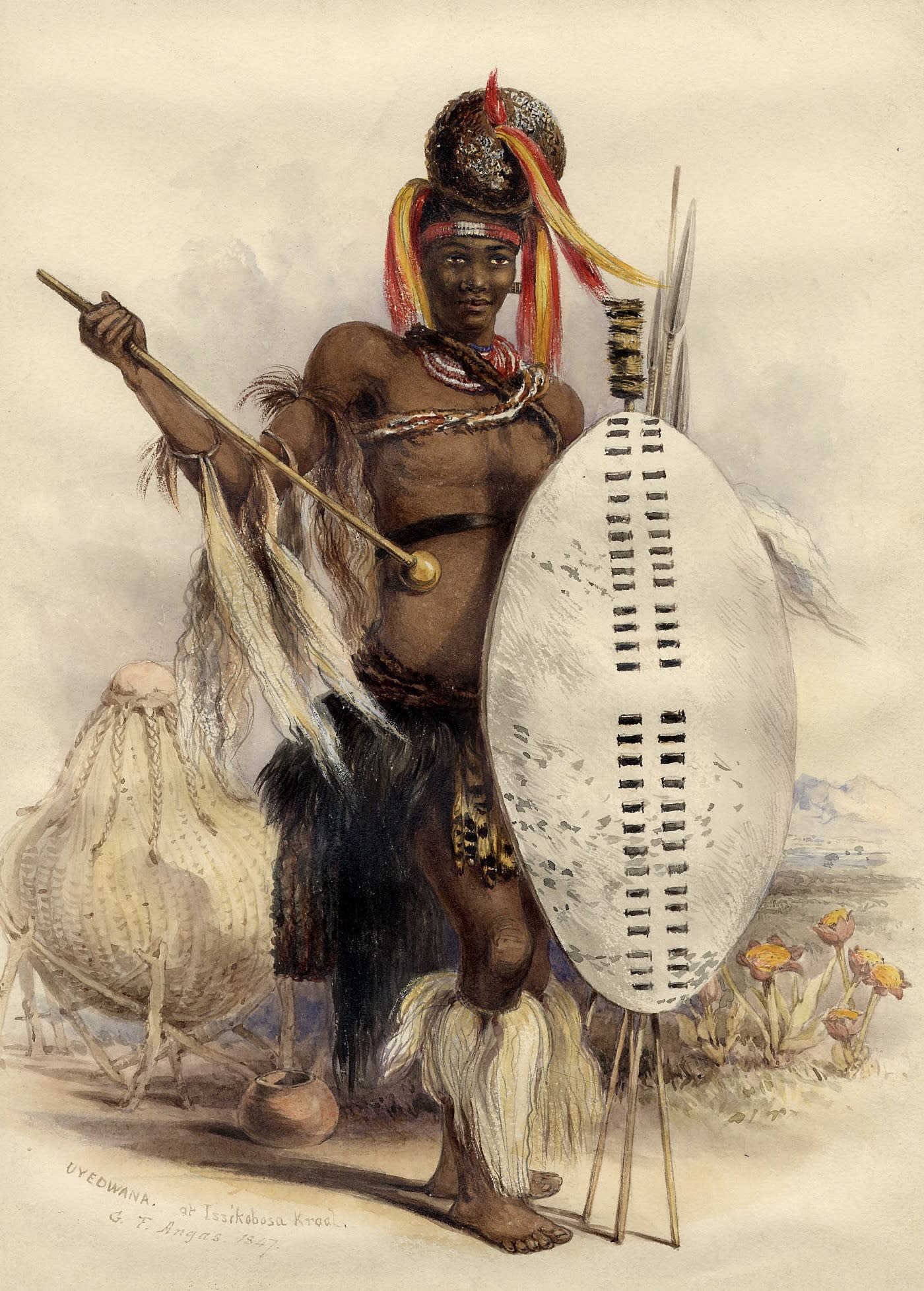

Though other European artists had ventured into Zululand, most notably the naturalist George French Angas (fig. 2) in 1847, Oerder was the first artist to portray the Zulu and their way of life from a non-ethnographic point of view. His works are markedly different from these ethnographic illustrations, depicting the Zulu simply as people, rather than as picturesque or ‘exotic’ beings. The small handful of genre scenes reveal the daily and unvarnished lives of the Zulu, cooking in the open (fig. 3) or eating porridge in a dark interior.

Fig. 2, George French Angas, Uyedwana, watercolour,

32.7 x 23.7 cm, British Museum

Fig. 3, Frans David Oerder, Zulus Cooking, oil on canvas,

46 x 40.5 cm, Private Collection

In the present work, a young man of tangible presence looks resolutely out at the viewer and has been painted by Oerder with rapid, impasto brushstrokes. The subject of the portrait is exceedingly rare not only within the artist’s oeuvre but also within the wider context of the time and constitutes one of the very earliest, if not the earliest, oil portrait from life of a Zulu man. A second, smaller, portrait of a Zulu man from the same trip (fig.4) appeared on the US market in the early 1990s and similarly depicts the sitter at half-length with a feathered headdress. Perhaps Oerder could be criticised for presenting these two Zulu men as a European audience would want to see them, dressed up in all their finery, from the ostrich-plumes to the cow-hide straps, beads and arm bangles. That said, a real sense of the sitter’s individuality and personality comes through in Oerder’s remarkable portrait.

Fig. 4, Frans David Oerder, Portriat of a zulu,

oil on canvas, 23 x 16 cm, Private Collection