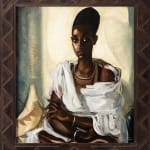

Clément Serneels (1912 - 1991)

Portrait Chief Rwampungu’s Wife

Signed, titled, located and dated: FEMME DU CHEF / WRAMPUNGU / KIGALI / Clément Serneels / 1939

Oil on canvas

80 x 71 cm (31 ½ x 28 in.)

Portrait Chief Rwampungu’s Wife

Signed, titled, located and dated: FEMME DU CHEF / WRAMPUNGU / KIGALI / Clément Serneels / 1939

Oil on canvas

80 x 71 cm (31 ½ x 28 in.)

Painted in Kigali in modern-day Rwanda in 1939, Clément Serneels’ portrait of the Tutsi chief Rwampungu’s wife can be considered an exceptional example of its type on account of its remarkable quality, fine condition and striking beauty.[1] More importantly still, outside of the Tutsi royal family, it is incredibly rare to be able to identify the sitter in a Rwandan portrait of this date and place them within the broader historical context, even if in the present work the sitter’s identity is known only through the name of her husband, a prominent Tutsi chief in the province of Kigali. In fact, in only a small handful of European portraits of Central African sitters over the first half of the twentieth century, can we know anything about the biography of those depicted, ensuring that the portrait of Rwampungu’s wife is not only a mesmerising image but also a historical document of some significance.

Clément Serneels, born in Brussels in 1910, was the son of a Belgian architect. He first visited the Belgian Congo and Ruanda-Urundi in 1936-37, though there was initial resistance from the Belgian minister of the Colonies due to the expensive nature of such travels. However, he was eventually granted the necessary finances thanks to the support of Alfred Bastien, the director of the Académie de Beaux-Arts de Bruxelles, where Serneels was one of his most brilliant students. Thanks to the success of the first trip, with a sell-out exhibition on his return to Belgium, Serneels travelled back to Central Africa in 1938, this time using his own resources. When World War II broke out, the artist stayed on in Costermansville (modern-day Bukava), on the south-west shores of Lake Kivu in the Belgian Congo.\

Fig. 1, Clément Serneels, Tutsi Intore Dancer, oil on

canvas, 80 x 70 cm, Private Collection

Rwampungu’s wife was painted by Serneels in 1939 at Kigali, about two-hundred and fifty kilometres to the east of Costermansville, situated amongst the rolling hills and valleys of central Rwanda. Today Kigali is the country’s capital, as well as its economic and cultural hub, though at the time it was a relatively small and recently founded regional centre. Serneels seems to have visited Kigali specifically to see the famous Tutsi dance festival, as confirmed by his image from the same date of an Intore dancer, whose performances were reserved for the King and his retinue (fig. 1). The dances would have allowed Serneels to spend time amongst the Tutsi elite, where he would have seen Rwampungu’s wife.

Though we do not as of yet unfortunately know her name, something of Rwampungu’s wife’s biography can be gleaned through her husband, a notable Rwandan chieftain. Rwampungu was the head of the Abatsobe clan and held sway over the province of Bumbogo, near Kigali, which was given by King Rwabugiri to his father Gashamura in the late 19th century. As head of the abiru, essentially a politico-ritualist council close to the king, Gashamura was a powerful figure in the Rwanda of the 1920s, occupying a position of importance second only to the ruling sovereign and queen mother. Due to his opposition to Christianity and the influence he was thought to hold over King Musinga, Gashamura was accused of witchcraft and exiled to Gitenga, in Burundi, in 1925.[1]

Thereafter, the Belgian administration initiated a decree forbidding all ancestral rituals connected to the king, eventually deposing Musinga in 1931, after his repeated refusals to convert to Christianity. Rwampungu was placed in a Belgian-run school in Nyanza for the sons of chiefs, and was baptised in 1928, taking the name Edouard. Like his father, he was one of the leading chiefs of Rwanda and close to the king. A photo from the mid-1930s shows a smiling Rwampungu standing next to King Mutara, successor to Musinga, who turns and grins at him, as they presumably share a joke amongst a group of other leading Tutsis (fig. 2). A bust-length photo of Rwampungu can also be seen in Léon Delmas’ Généalogies de la Noblesse du Ruanda.[2] Rwampungu frequently appears in the official notes of the Belgian governors and administrators, which describe some of his territory and the under-chiefs who reported to him, as well as mentioning a long-standing conflict between Rwampungu and his brother Kagango over land.[3]

Fig. 2, Anonymous photograph of c. 1935, King Mutara and Rwampungu, with other

Tutsi chiefs

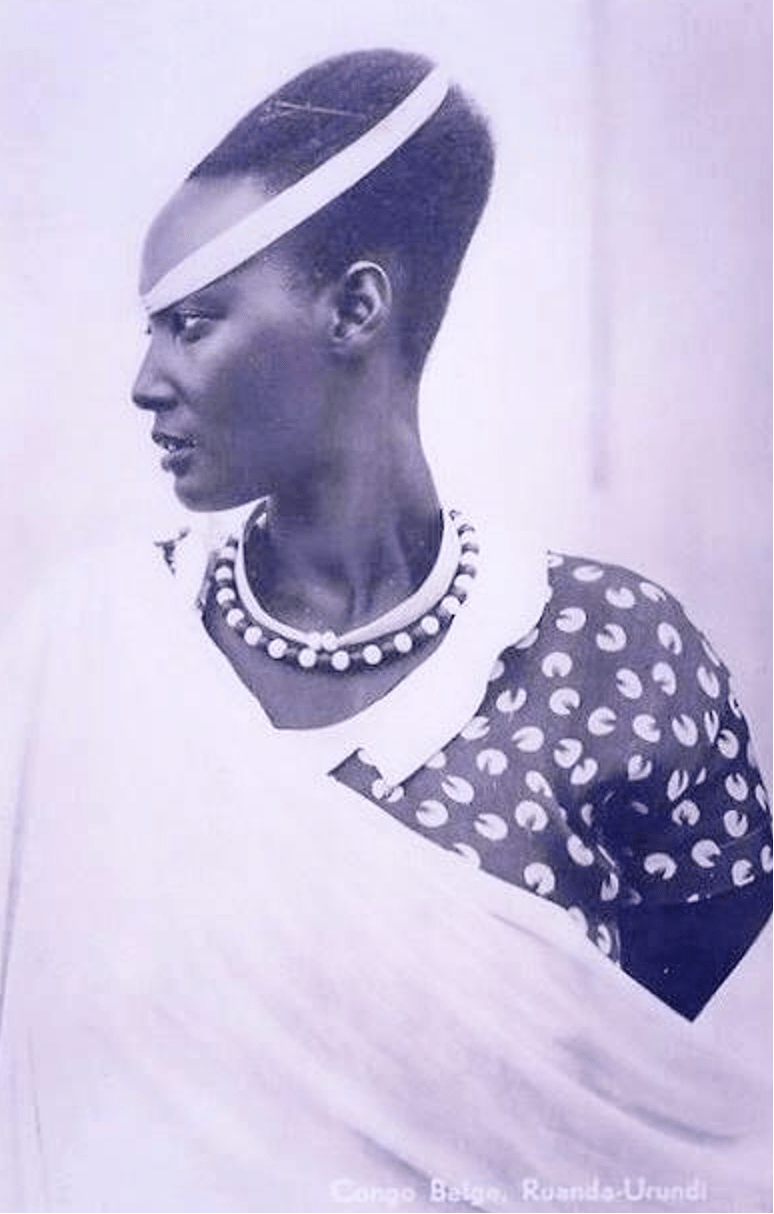

When Serneels painted Rwampungu’s wife in 1939, she would therefore have been the most important woman in Kigali province, and indeed one of the most prominent in Rwanda as a whole, surpassed only by the Queen, the Queen Mother and the princesses of the royal family. She must therefore have been a leading figure at the dance festival, which took place in her home territory. This, alongside her striking beauty, was probably what led Serneels to paint her. Her exalted status is evident from her attire: voluminous white fabric draped toga style around the shoulders; upswept, bouffant hair; and copper bangles around the neck and wrists. These elements are consistent with other images of privileged Tutsi women from the time, as can be seen, for example, in a photograph of Princess Emma Bakayishonga (fig. 3) or indeed in Irma Stern’s portrait of her from 1942 (fig. 5 ). Serneels places his sitter next to a traditional Tutsi basket of the itana (‘tip of the arrow’) pattern, whose tapering lid mirrors the elongated forms of Rwampungu’s wife. Amongst the Tutsi elite, women were responsible for weaving refined baskets of this type, and did so as a communal activity, often accompanied by the sound of music performed by Tutsi harpists.

Fig. 3, Anonymous photograph of c. 1940, Princess

Emma Bakayishonga

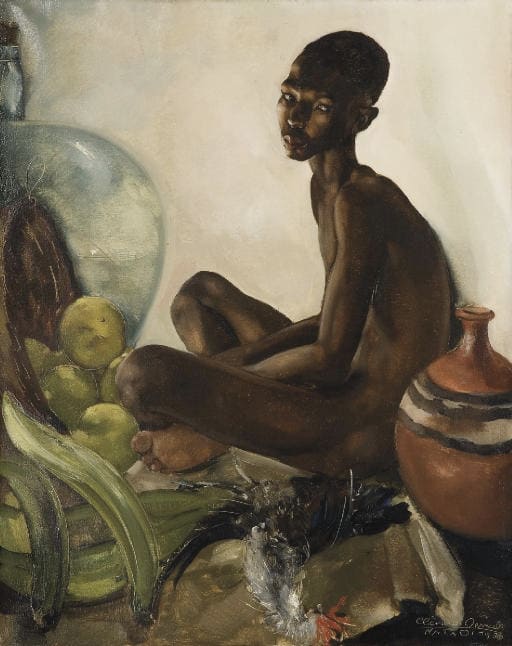

Unlike Stern, with her contemporaneous notes, we are unable to definitively determine Serneels’ thoughts on the Tutsi, and on Rwampungu’s wife in particular. Yet, a reading of the portrait itself would suggest that Serneels, like many of his fellow painters and countrymen, was mesmerised by the physical aspect of the Tutsis, perceived or otherwise. Serneels clearly took delight in his sitter’s ‘noble bearing’ and ‘aristocratic beauty’, both of which he emphasised by placing Rwampungu’s wife against a neutral background. The drapery, created through liquid and virtuoso brushstrokes, contrasts with the detail of her face, further accentuating its forms and structure. The result is an image which easily stands alongside Serneels’ most striking works from all his years in Central Africa (fig. 4), and should be considered amongst his most important paintings. In fact, it can be seen to be one of the most significant paintings of a Rwandan, and indeed Central African, sitter of this period, alongside Irma Stern’s depictions of the Tutsi royal family.

Fig. 4, Clément Serneels, Young man from Matadi,

oil on canvas, 101 x 81 cm, Private Collection

Irma Stern visited Rwanda in 1942, after having passed through the Belgian Congo. Her stay in Rwanda is well-documented, thanks to her journal and the numerous letters she wrote whilst there and, though we cannot speak for Serneels, these sources, which eulogise the physical attributes of the Tutsis and muse upon their ‘high-culture’ and ‘ancient origins’, articulate the allure the Tutsis held for many Western artists.

Like Serneels, Stern visited Kigali for the annual Fête Nationale, enthusing that she had ‘painted the king and queen and the queen mother of the Watussi. Their movements were dignified beauty, their features – long-necked, long-faced - were exquisite, a beautiful and timeless majesty. Here I had found, as I thought, the quintessential of beauty’.[1] In her journal, published in 1943, she described her visit to the Royal Box: ‘There sits the Queen Mother…She looks like an Egyptian statue. Next to her, in flowing white garments, sits the young and beautiful new queen…Her hair is a huge arrangement of black, just perfectly proportioned to the size of her long oval-shaped head. She purses her lips as the Egyptians did. From beneath her long flowing robe her bare foot emerges. Never have I seen such beauty; it is like the black basalt foot of an Egyptian statue. It is expressive of a highly-bred cultured ancient race.’[2]

Fig. 5, Irma Stern, Princess Emma Bakayishonga, oil on canvas,

86 x 86 cm, Private Collection

Though Stern’s words feel outmoded today, they perhaps sum up what Serneels felt and saw as he painted Rwampungu’s wife, creating a picture of outstanding beauty and importance for its time and place.

[1] D. Byanafashe and P. Rutayisire, History of Rwanda. From the Beginning to the End of the Twentieth Century, Kigali 2016, p. 243.

[2] L. Delmas, Généalogies de la Noblesse du Ruanda, Kabgayi 1950, p. 121.

[3] Territoire de Rubura [Rukira?]. Rapport etabli en reponse au questionnaire adresse en 1929 par M. le Gouverneur de Ruanda-Urundi a l’Administrateur du territoire de Rubura, M. Massart. 1929, p. 18.