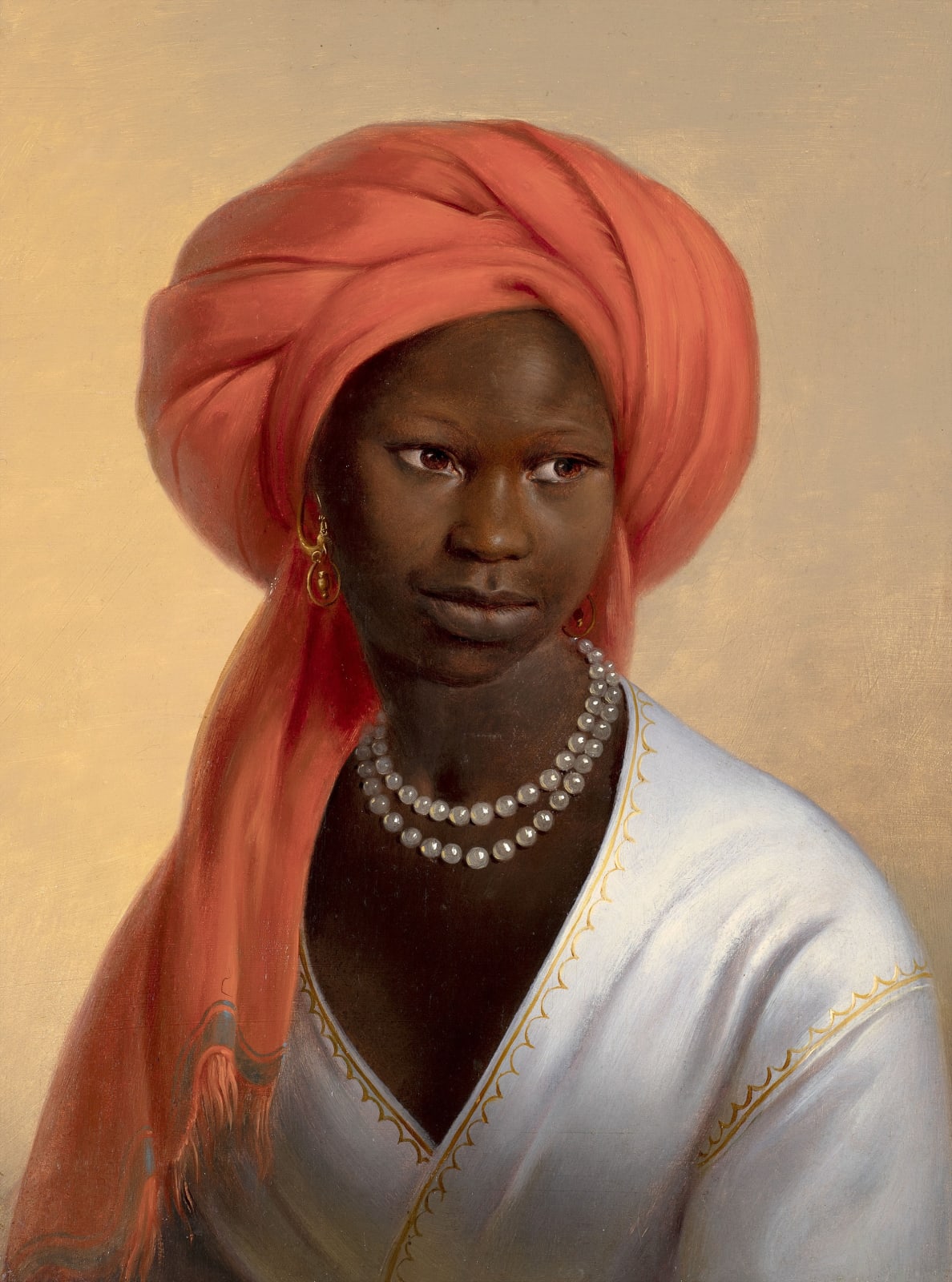

Anton Grüss (1802 – 1875)

Portrait of a woman in a red turban

Signed and dated lower left: Ant: Gruss 1844

Inscribed on the reverse in a later hand: Jesenice / Cirova

Oil on panel

Portrait of a woman in a red turban

Signed and dated lower left: Ant: Gruss 1844

Inscribed on the reverse in a later hand: Jesenice / Cirova

Oil on panel

32.2 x 24.4 cm. (12 ¾ x 9 ½ in.)

Provenance:

Private Collection, Wurzberg.

This portrait of a Black woman in a red turban, dated 1844, is a remarkable rediscovery. As one of the only known depictions of a Black sitter from the Habsburg Empire at this time, it is an incredibly rare and significant work within an Austrian, and indeed Germanophone, context. Its appearance therefore raises many important questions about the presence, and place, of Black people in the Habsburg lands in the first half of the nineteenth century, as well as the identity of the sitter herself. Beyond its contextual importance, the painting is a welcome addition to the oeuvre of the little-known Bohemian artist Anton Gruss. Due to the partial illegibility of the signature, the portrait had lost its attribution when it was acquired at auction in Germany. However, comparing the signature to an 1842 portrait by Gruss of an officer leaves no doubt that he is the author of the present work (figs. 1 and 2).

Fig. 1, Anton Gruss, Portrait of Anton von Lillien,

1842, oil on canvas, 90 x 71 cm, Private Collection

Fig. 2, Detail of signature

Gruss was born in 1803 in the Bohemian town of Varnsdorf, then part of the Austrian Habsburg Empire. His brother Johann, a decade older, was also an artist and encouraged Gruss to pursue this profession, teaching him the basics of painting. By 1825 Gruss had moved to Prague, formerly the Habsburg capital and still one of the largest urban centres after Vienna and Budapest. Here he studied at the prestigious Academy of Fine Arts under the tutelage of the Czech painter František Tkadlík, whose Nazerene-inspired style and strong colouring would have a marked impact on the young artist. Gruss finished his arts education by travelling through Germany and Italy, returning to Prague in 1838. He began to make his reputation in painting altarpieces for churches in and around the city, though also specialised in portraits, miniatures and landscapes. At some point he formed a long lasting connection with the Harrach family, serving in their household as an arts tutor. The Harrach were an influential Bohemian noble house, one of the most prominent families in the Habsburg Empire, with extensive estates and palaces across the Austrian lands. Eventually Gruss was promoted to the directorship of the Harrach Gallery in Vienna, cataloguing the family’s important collection in 1856 and continuing to make new acquisitions.

In the present work Gruss depicts a Black woman wearing a volumetric red turban, with a double string of pearls around her neck. She also wears gold earrings and a blue robe, probably of silk. Her features are individualised, which very much suggests that Gruss is painting from a model and this picture is therefore essentially a portrait. Whilst the identity of Gruss’s model remains unknown, the most informed suggestion we can make, going by the contextual evidence, is that the sitter is a domestic servant in the Harrach household. There was a small, though non-negligible, Black population in the Habsburg Empire at this time. Their presence there was primarily due to the longstanding desire amongst the aristocracy to ‘exoticize their public as well as private lives’[1] through the use of Black servants.[2] Known as hofmohren, the use of Black servants amongst the imperial family and Austrian elites became a trend in the closing decades of the seventeenth century when, interestingly for our purposes, Count Ferdinand von Harrach returned to Vienna from his ambassadorial role in Spain with several dark-skinned domestics, including two women, named Paula and Emanuela.[3] These hofmohren gave prestige to their aristocratic owners and were purchased through overseas slave trading channels, primarily via Portugal and later through the British West Indian colonies.

Fig. 3, Albert Schindler, Portrait of Emmanuel Rio, 1836,

oil on panel, 39 x 32 cm, Art Institute of Chicago

The closure of the European slave trading networks at the end of the 18th century changed the dynamics of procuring Black servants, who were now acquired directly by noble travellers to Ottoman lands or sent from Brazil. Following the prohibition of slavery in the Habsburg lands in 1811, these servants were automatically considered free men or women once they set foot on Austrian territory, though the notion of personal freedom may have remained an irrelevant concept in practice, dependent as they were on the families they served. These servants mostly arrived as young boys, though there were a few female exceptions. The best-known case of a Black servant in Austria from the first half of the 19th century is that of Emmanuel Rio (fig. 3), an Afro-Brazilian who arrived in Vienna in 1820 at the age of about ten years old. He had been sent from Brazil to the Emperor Francis, who enrolled him in an elite private school where he excelled in languages, drawing and especially music. Despite these skills, Rio was assigned to work in the imperial garden. An 1836 painting of Rio, by Albert Schindler, depicts him with his French horn, surrounded by gardening equipment. This is one of the only other known images of a Black sitter in Austrian painting from this time, further highlighting the importance of Gruss’s picture.

Bearing the above in mind, and as already mentioned, the most likely scenario is that the sitter in Gruss’s portrait is a domestic servant of the Harrach family, painted perhaps in either Vienna or Prague.[1] As members of the Habsburg elite, the Harrachs would have had the resources, as well as the predilection, to employ a Black female servant. Indeed, this would even be in keeping with family tradition, given the examples of Paula and Emanuela cited above. Also, the inclination for their household artist to capture her features would not be unique to them, as the example of Emmanuel Rio demonstrates. If this hypothesis is correct, the name of the sitter may well be mentioned in the extensive Harrach archives in Vienna.

The identity of the sitter aside, Gruss’s portrait ties in more broadly with the romantic appeal of foreign lands and peoples then prevalent in European art, particularly in France. Perhaps the closest compositional comparison to Gruss’s work is Eugène Delacroix’s 1827 depiction of a non-European model in a blue turban (fig. 4). In both works the sitters possess a solemn dignity and are set against an orange, dusky backdrop, possibly representing more tropical skies. The turban and jewellery in Delacroix’s image are likely studio props, used to emphasise to the foreignness of the sitter. This is probably the case also in Gruss’s picture, as by this date the fad for dressing Black servants in Orientalising costume was fading.

Fig. 4, Eugène Delacroix, Portrait of a woman in a blue

turban, 1827, oil on canvas, 60 x 49 cm, Dallas Museum of Art

These motifs, as well as tying in with contemporaneous Romantic concerns, find precedence in allegorical works of the previous centuries. For example, we may compare Gruss’s painting with Rosalba Carriera’sAllegory of Africa (fig. 5) from circa 1720, then, as now, in Dresden. Here, once again, the jewellery and turban emphasise the ‘exoticness’ of the figure. However, the notable difference, and what really makes Gruss’ picture noteworthy, is that in his image we are looking at a real person, painted from life, rather than a more generic and idealised depiction, as is the case with Carriera’s pastel and other allegories of this nature.

Fig. 5, Rosalba Carriera, Allegory of Africa, c. 1720,

pastel, 34 x 28 cm, Gemäldegalerie Dresden

A further influence on Gruss’s portrait may well be a famous engraving from circa 1750 depicting Angelo Soliman (fig. 6). Originally from West Africa, Soliman achieved prominence and success in Viennese society and intellectual circles during the 18th century, becoming chief servant and tutor within the Princely Liechtenstein house, and later served as Grand Master of a Masonic Lodge. Soliman married a noblewoman and was valued as a friend by the Emperor Joseph II. Holding a baton and set against a landscape of pyramids and palm trees, Soliman looks resolutely out at the viewer. As in Gruss’s work, Soliman wears a turban and is presented against the hazy sky of the tropics. The engraving was widely disseminated and Gruss would have very likely have known it.

Fig. 6, Gottfried Haid after Johann Nepomuk Steiner,

Portrait of Angelo Soliman, 1750, engraving

Taking all the above in consideration, and whether the sitter is a member of the Harrach household or not, Gruss’s portrait is an extremely rare and significant work within the context of Austrian 19th-century painting, opening up many important lines of enquiry with regards to the Black diaspora in Habsburg Austria.

We are grateful to Dr Walter Sauer and Dr Lucie Storchova for their help with this note.